When San Francisco architect Stephen Sutro was asked to name his favorite legendary Bay Area architect, he didn’t hesitate: William Wurster.

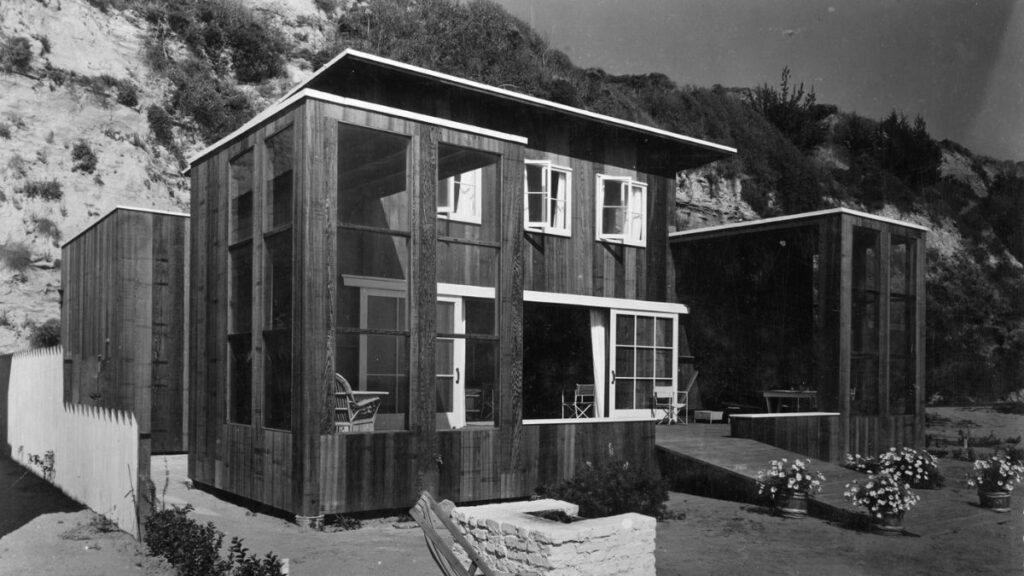

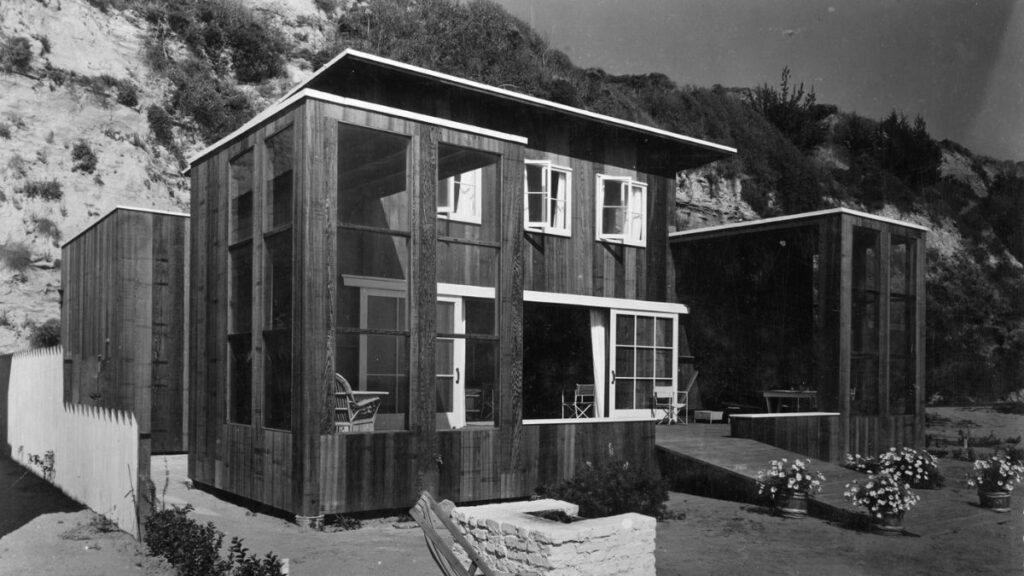

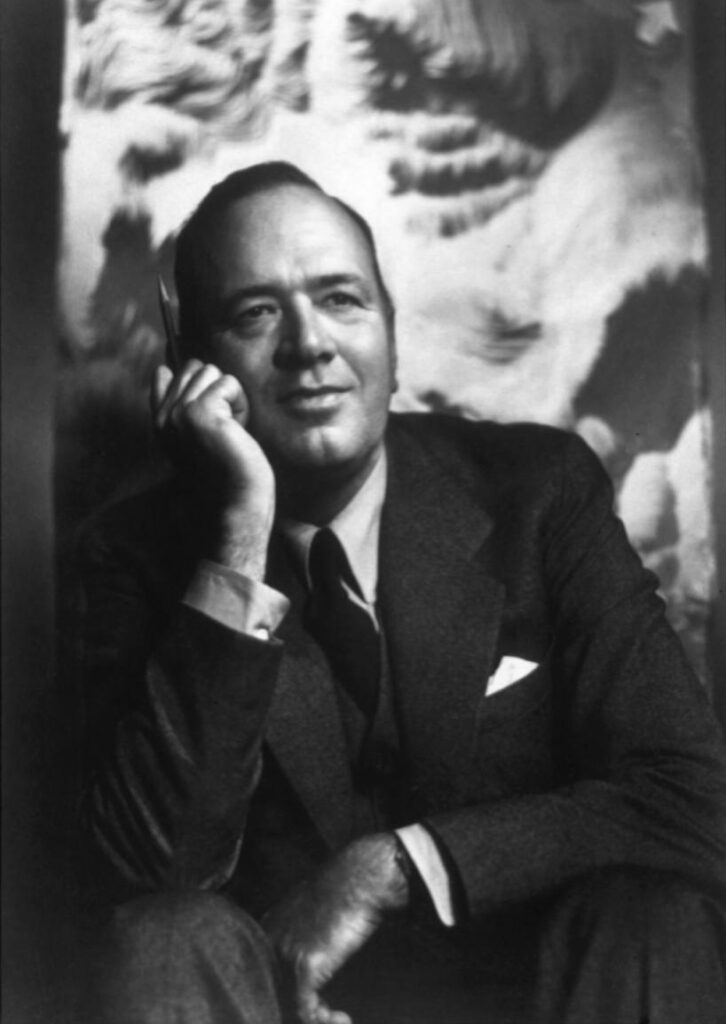

Born in Stockton in 1895, Wurster helped define the Bay Region Style rather than replicate the International Style emerging from Europe. He championed a distinctly Californian modernism defined by climate and lifestyle — emphasizing indoor–outdoor living, cross-ventilation, shaded porches, and an easy relationship to the landscape.

Rather than importing materials or imposing abstract forms, Wurster worked with local redwood, wood siding, and brick, carefully integrating his buildings within their surroundings. Responding to the Western way of life, he designed informal, comfortable spaces that were modern yet regional — warm, intuitive, and deeply human-centered.

Along with Stephen Sutro, Amplified Lifestyles admires how Wurster made Modernism truly livable. His work combined practical floor plans, flexible open interiors, abundant natural light, and natural airflow — all grounded in an emphasis on comfortable domestic life. His homes were modern without feeling radical or alien. They felt natural.

Wurster helped normalize modern design for middle- and upper-class residential clients, transforming it into something people could inhabit with ease rather than simply admire. In many ways, he softened Modernism — making it more regional, humane, and environmentally responsive long before “sustainability” became a formal concept. By bridging the Arts & Crafts traditions of Bernard Maybeck and the International Modernism of architects like Richard Neutra, he created a meaningful transition between the two and influenced later environmental and contextual design movements.

This Spring Break, Amplified and some of their collaborators made a pilgrimage to Scottsdale and Frank Lloyd Wright’s Taliesin West. Lutron invited them to see their innovative installation of Ketra’s lighting system. Wright, a pivotal 20th-century architect, built Taliesin West as his winter camp in 1937. The Desert Studio educated students through apprenticeship and hands-on learning. Located in the foothills of the McDowell Mountains, Wright blended organic architecture seamlessly with the topography, utilizing desert masonry and geometric forms, giving the structures a prehistoric grandeur. Negative space, natural light, and a reflecting pool further pierce the veil between the interior and exterior worlds.

Lutron was honored to work on the UNESCO World Heritage site and National Historic landmark. They faced the challenge of replicating “lantern-lit” light, Wright’s vision, which he achieved through natural light, firelight, and low-wattage incandescents that echoed the spectrum of the desert landscape. Ketra was the perfect solution to deliver a consistent quality of color-matched light. The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation also required that the installation not damage or alter the existing buildings or wiring infrastructure; they could not drill into the stone walls and the fragile vintage light fixtures needed special handling.

Ketra’s wireless technology preserved Wright’s masterpiece for future generations to learn from while improving the visitor experience. The system provides high-quality light that is flexible and adjustable, allowing for bespoke settings that gradually shift in color, temperature, and intensity to mimic the sun, making interiors feel seamlessly bathed in natural light. As Wright envisioned, Taliesin West’s organic architecture sits easily on the land, and Ketra illuminates its nuances. The Amplified team and their guests enjoyed seeing Lutron’s restoration of the World Heritage site firsthand and the replication of Wright’s “lantern-lit” light.

We think of Lutron Electronics as a technology-driven company, but its co-founder, Joel Spira, was equally fascinated by aesthetics and how light affected mood. In 1959, the young physicist worked from a spare bedroom in his Manhattan apartment and developed the solid-state dimmer. He called his invention Capri and aimed his marketing efforts toward women, not electricians. Spira repurposed the original elegant gold package displaying the Lutron logo and verbiage from an overrun of perfume boxes. With a turn of the Capri knob, the homeowner could light up, mimicking bright sunlight, or light down to imitate the flicker of romantic candlelight.

The idea was radical then; residential lighting control didn’t exist. It was limited to theaters and stage lighting because it required expensive, bulky rheostats that wasted energy and were challenging to install. Lutron’s family of offerings grew, and from their Pennsylvania headquarters, Spira developed a litany of lighting controls that integrated into a home’s design, providing functionality while highlighting architectural details.

In 1971, he introduced Nova, the first linear slide dimmer. In 1989, Lutron followed this with RanaX, the first infrared remote control dimmer. The next evolution was the 1990 NeTwork, the first whole-home lighting control system. Later, network-style dimming products ensued, including the customizable GRAFIK Eye in 1993 and the RadioRA in 1997, which operated wirelessly using radio frequencies. In the late ’90s, Lutron added HomeWorks, which became the industry standard for residential lighting control. With the addition of automated shades, the company controlled solar lighting and electricity.

Lutron was always a family business; Sprira co-founded the company with his wife, Ruth Rodale Spira. Mrs. Spira handled Lutron’s marketing efforts, including the “dial-up romance” ad campaigns for the Capri. The company expanded its offerings to encompass window shading systems and energy-conscious devices. But Spira was always remembered for pioneering the dimmer. When he passed away in 2015, his New York Times obituary stated he “changed the ambiance of homes around the world and encouraged romantic seductions of all types.” His wife died in 2019.

Today, Spira’s daughter, Susan Hakkarainen, is Chairman and CEO of Lutron Electronics. She started as an engineer with a BS and MS in Electrical Engineering from Cornell University and a PhD in Applied Plasma Physics from MIT. She soon went on to international assignments and more senior roles. Sharing her mother’s aptitude for marketing, she became CMO. As Chairman and CEO, Hakkarainen continues Lutron’s commitment to world-class quality and service standards and promotes its position as the leader in smart lighting and shading control solutions. Her philanthropic endeavors include serving as a Trustee of the Asia Society, on the Advisory Board of The Wolfsonian–FIU, and as a former Trustee of Pratt Institute.

Shades of Pink: Arquitectonica’s Pink House

Before the Barbie film exploded on screens with a color palette of 100 different shades of pink, Arquitectonica created Miami Shores’ Pink House in 1978. The waterfront villa, fabricated from concrete and clad in stucco with glass-block windows and a voyeuristic porthole, echoed South Florida’s Art Deco and Modernist architectural vernacular. Its architects, husband and wife team Bernardo Fort-Brescia and Laurinda Spear boldly painted its planes in five shades of pink ranging from a whisper to near red. An exterior row of royal palm trees and an interior lap pool complete the tropical cadence. The project helped launch their Coconut Grove-based firm. Today, Arquitectonica is a global company.

Miami of the seventies was no longer the Magic City that vacationers flocked to post WWII through the sixties. South Beach’s Art Deco district sat decaying with hotels falling victim to the wrecking ball. The city became known for elderly retirees and violent Cocaine Cowboys. At Miami’s lowest point, in 1981, it was the crime capital of the US. Arquitectonica’s Pink House signaled a cultural change. Its status went beyond the architectural academia of Progressive Architecture and Domus when mainstream publications featured it. The New York Times, Life, Time, Newsweek, House Beautiful, Vogue, and GQ showcased its rosy hues and edgy lines. In 1984, the new crime drama TV series Miami Vice chose the Pink House for the home of an arms dealer played by Bruce Willis.

Miami Vice displayed Arquitectonica’s glass-clad, primary-hued Atlantis condominium building in its opening credits. The Biscayne Bay high rise, with a touch of magic realism, boasts a cut-out five-story sky court that includes a palm tree, a red spiral staircase, and a round pool. Its architects, the Peruvian-born Fort Brescia, and the American Spear represented the city’s cosmopolitan mix. They brought Miami academic credibility with Ivy League educations, Fort-Brescia from Princeton and Harvard, and Spear from Brown and Columbia. Their work pierced the Miami skyline and the international psyche. Arquitectonica now has offices in eleven cities in the US and beyond; it started with the Pink House.

The Wright Way: Frank Lloyd Wright’s Northern California

Frank Lloyd Wright’s Marin County Civic Center etches the landscape, and his Maiden Lane Mousetrap has had as many lives as the two white Persian cats who once lounged there. Wright’s Northern Californian residences are equally as evocative. The Wisconsin native, who passed away in 1959 at 91, enjoyed a creative relationship with the Golden State. His Carmel by the Sea project, known as Mrs.Clinton Walker House, designed in 1948, resembles a ship with its bow cutting through the ocean. Della Walker requested a home “as durable as the rocks and as transparent as the waves.” Constructed of cedar and Carmel stone and on the National Register of Historic Places, the property recently sold for $22 Million.

The Hanna–Honeycomb House on the Stanford University Campus, recognized as a National Historic Landmark, was Wright’s first work in the Bay Area. Started in 1937 and expanded over 25 years; the architect patterned the design after a bee’s honeycomb. The one-story structure clings to the hillside on a one and half acre site. Wright selected native redwood board and batten, wire cut San Jose brick, concrete, and plate glass for the construction, which included a main house, guest house, hobby shop, storage building, double carport, garden house, pools, and water cascade. The Hanna family lived there for 38 years before giving the property to Stanford University in 1974.

Wright strongly believed in creating dwellings for middle-class Americans he called Usonian homes. One was the mid-century owner-built Berger House in San Anselmo which he designed for Robert Berger, a mechanical engineer, his wife Gloria, and their four children. The stone, glass, wood, and concrete residence, which cost $15,000 to construct plus Wright’s $1,500 fee, was listed for $2.5 Million in 2012. Berger worked building the home for twenty years until he died in 1973. His widow hired a professional carpenter to finish the project, including Wright-designed furnishings. One element did not survive to the present; Edie’s House, a dog shelter that Wright designed for the family’s Labrador Retriever. Unfortunately, Edie preferred the main house, and the canine home was taken to the dump.

The Timeless Appeal of Eichler Homes

Amplified Lifestyles has long admired the California mid-century Eichler Homes built by developer Joseph Eichler (1900 – 1974). These light-filled houses are recognizable for their recessed entryways with broad, low-gabled roofing. While small windows faced the street for privacy, large picture windows at the back look to unobstructed views of the outdoors. Wood entrances, exteriors, paneling, and exposed widely-spaced posts and beams further emphasize the house’s connection to the natural world. To streamline the interiors, the developer utilized built-in furnishings and appliances. Open-concept kitchen, dining, and living areas, sometimes with glass partitions and central atriums, allowed homeowners to blur the line between the inner and outer worlds.

Eichler did not begin his career as a real estate developer but as a purveyor of butter and eggs. The native New Yorker moved to the San Francisco Bay Area in 1925 to help with his in-laws’ wholesale business. By 1943 he owned a retail store Peninsula Farmyard specializing in eggs and poultry. At the time, he and his family rented the Sidney Bazett House in Hillsborough, a Usonian-style residence designed by Frank Lloyd Wright. The experience of living in a Wright house inspired Eichler to create communities of homes that incorporated modern architectural elements for the average family. With millions of soldiers returning from WWII, the time was right.

In 1949, Eichler Homes, Inc. started building affordable residences designed by the Bay Area architects Robert Anshen and Steve Allen of the architecture firm Anshen and Allen. The architects masterminded the California Modernist style of the homes that first went on the market for an average sale price of $12,000. Later Eichlers were designed by Claude Oakland, A. Quincy Jones, and Raphael Soriano. Having experienced discrimination in New York for being Jewish, the developer advocated fair housing, selling homes to Asians and Blacks. Between 1949 and 1966, Eichler Homes built over 11,000 houses, primarily in San Francisco Bay Area suburbs. Today, their timeless appeal endures.

Arthur Elrod: Design Innovator

Not only did interior designer Arthur Elrod define Palm Springs Modernism, but he was also fascinated by new technology. In 1952 he moved to San Francisco for a two-year stint at the high-end furniture store W & J Sloane. Elrod designed an innovative exhibit to celebrate General Electric’s Diamond Jubilee of Light, transforming the San Francisco Museum of Art galleries into a penthouse apartment and terrace. For a contemporary look, Elrod selected furnishing from the British architect and designer T. H. Robsjohn-Gibbings. Instead of adding lighting as an afterthought with fixtures, he integrated it into the design. Inspired by the night sky, a downlight color constellation changed hues while concealed dimmer controlled spotlights.

After the GE exhibit, Elrod continued to create visually and technologically advanced interiors with sophisticated lighting and sound systems. He opened his eponymous firm in 1954 at 28, developing a clientele of Hollywood elite and wealthy individuals in Palm Springs and across the country. The design studio employed monochromatic color schemes to complement their clients’ impressive art collections or utilized saturated color blocking. Lighting elements and stereo speakers hid away within the custom furnishings.

Elrod and his associate William Raiser tragically died in a Palm Springs car accident when another vehicle struck their Fiat. At 49, he was still in his prime as a designer. Modernism enthusiasts best remember the designer for his residence, the futuristic Elrod House built by Googie architect John Lautner in 1965 and immortalized in the 1971 James Bond film Diamonds Are Forever. The home features a space-age concrete dome above the main living area. Its circular glass design with an outdoor swimming pool and terrace provides San Jacinto Peak and Palm Springs views.

At the time of his death, Elrod planned interiors for the volcanic-shaped hilltop villa that Lautner designed for Bob and Dolores Hope overlooking Palm Springs with views of Coachella Valley. While he did not complete this project, he created mid-century getaways for many notable clients, including Walt Disney, Frank Capra, Claudette Colbert, Laurence Harvey, Jack Benny, Lucille Ball, and Desi Arnaz.